Inheritance and Polymorphism in Java

Describe why inheritance is a core concept of object-oriented programming (10 minutes)

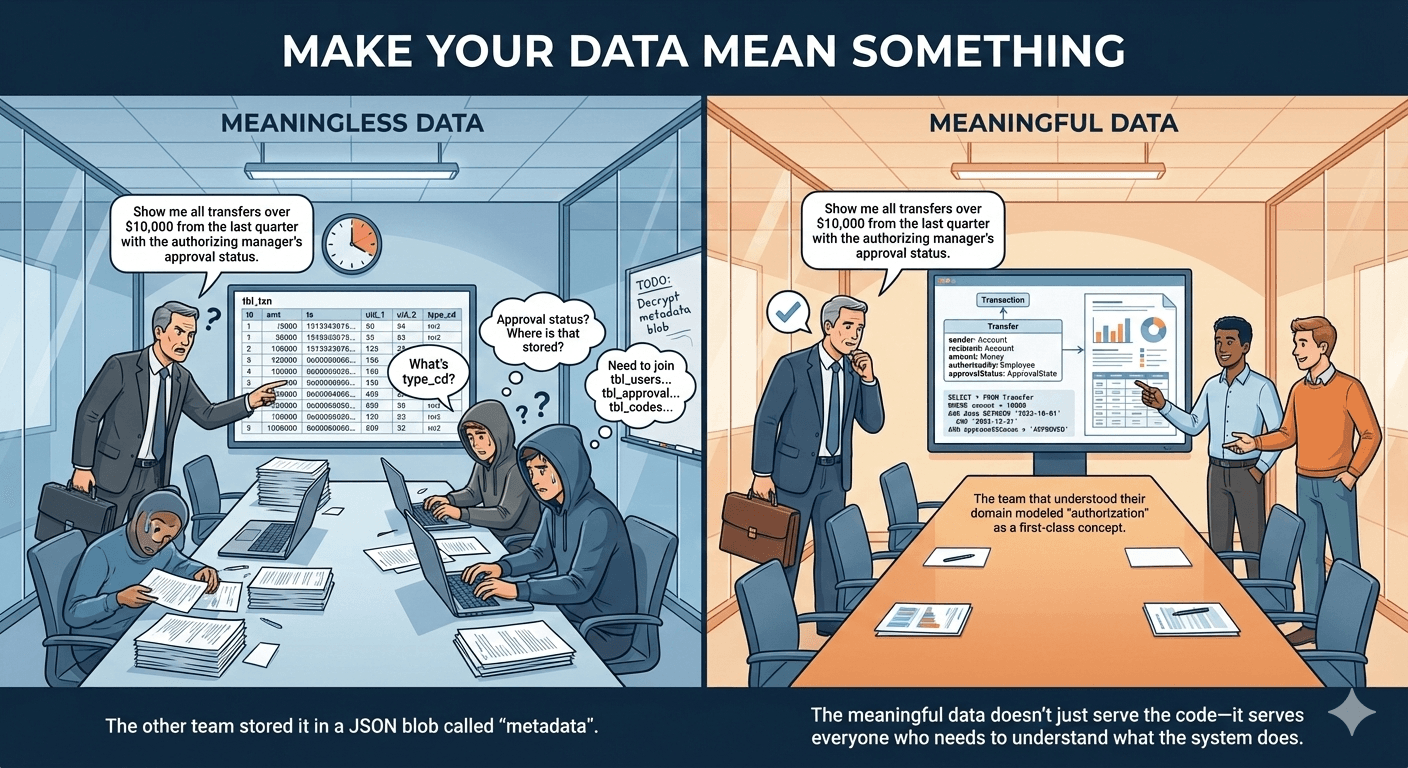

- A core principle of program design is: make your data mean something.

- We write software that manipulates data in some way, and oftentimes this data is related to some real-world concept.

- When it comes to designing our program, we can leverage our domain knowledge of that real world concept to design a program that is both easy to understand and easy to maintain.

- Inheritance is a core concept of object-oriented programming that allows us to model real-world "is-a" relationships between types.

- Duplicating code is a bad idea, because it makes our program harder to maintain. Inheritance allows us to reuse code across multiple classes that have the same behavior.

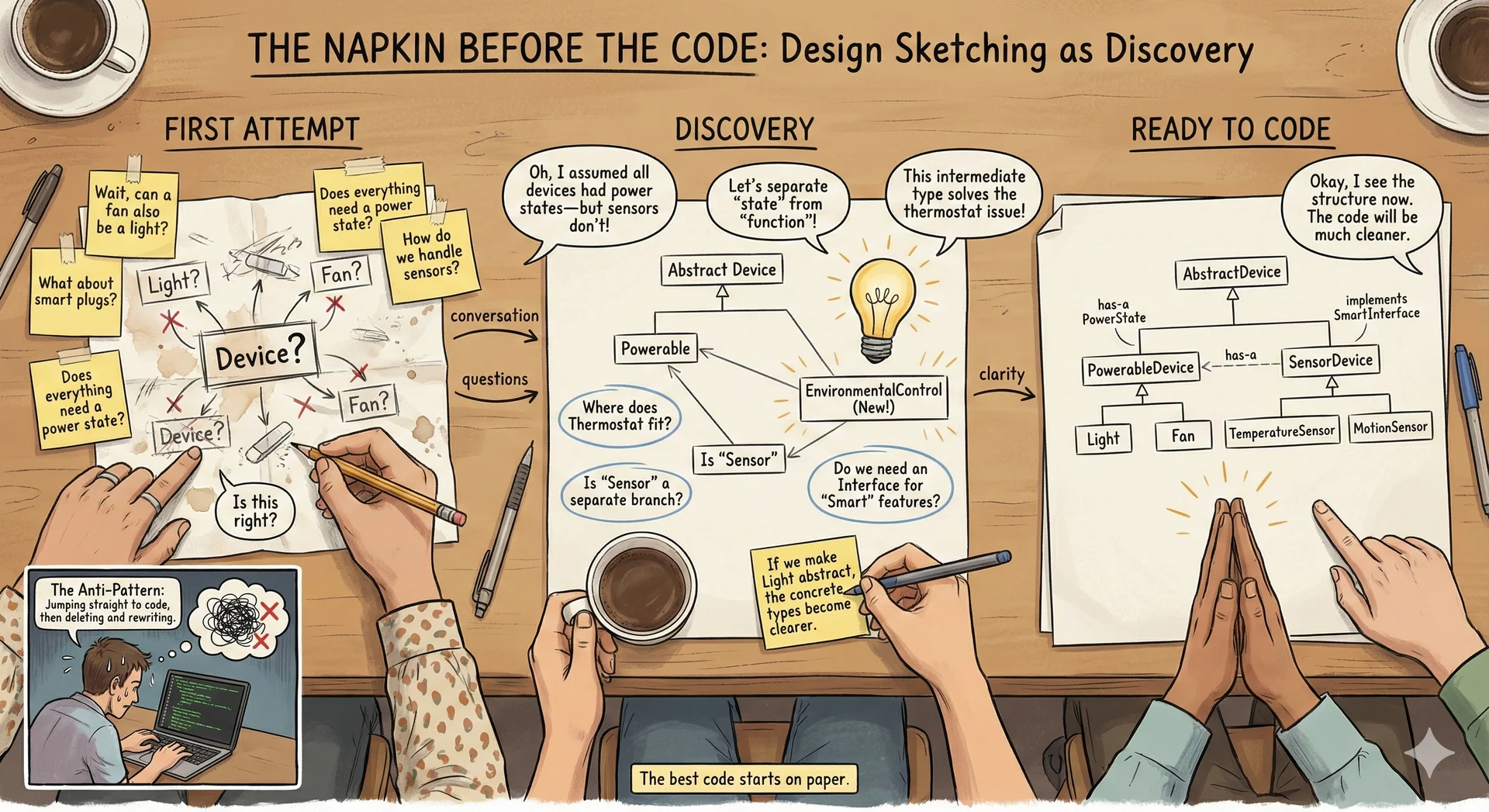

Here is an example inheritance hierarchy, in the domain of IoT (for brevity, we don't repeat inherited methods in each subtype).

At the top is IoTDevice, an interface that defines two methods all devices must implement: identify and isAvailable.

The identify method is intended to help a human identify the device by, e.g., flashing a light on it.

The isAvailable method is intended to check if the device is currently available to be used (e.g. if it is reachable over the network).

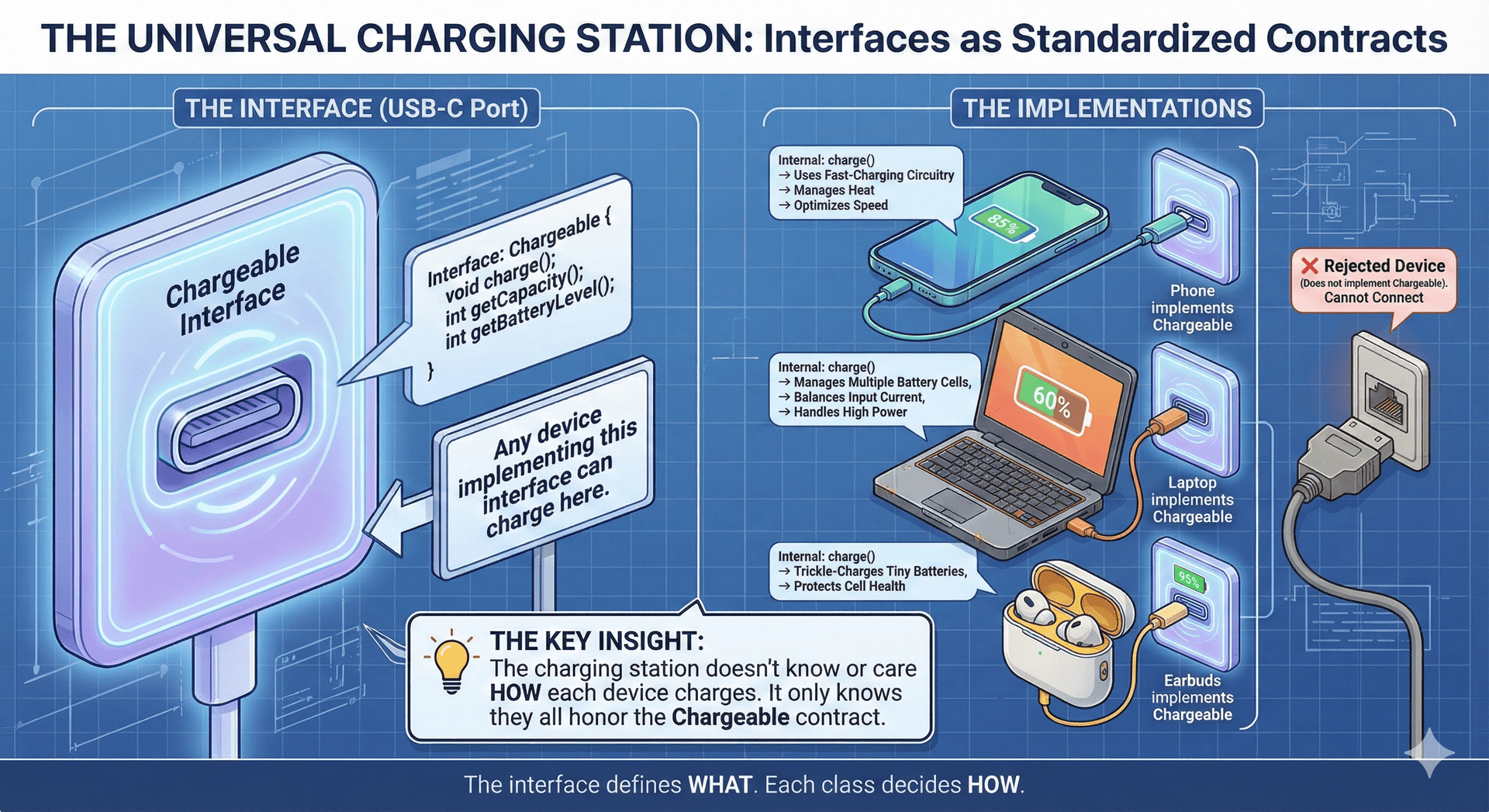

We declare this type as an interface because we want to define a contract without committing to a specific implementation.

BaseIoTDevice is an abstract class that provides a skeletal implementation of the IoTDevice interface. It implements isAvailable() (checking if the device is connected), but leaves identify() abstract since each device type identifies itself differently based on its hardware.

Light is an abstract class that extends BaseIoTDevice and adds light-specific behavior: turnOn(), turnOff(), and isOn().

Fan is a concrete class that extends BaseIoTDevice directly.

SwitchedLight and DimmableLight are concrete types that extend Light. DimmableLight adds brightness control.

TunableWhiteLight is a concrete type that extends DimmableLight to support not only dimming, but also adjusting the color temperature.

By structuring our program in this way, we can reuse code across multiple types that have the same behavior.

Every language has its own way of representing type hierarchies. In Java, type hierarchies are represented using classes and interfaces. Next, we'll look at classes, and then at interfaces.

Define a type hierarchy and understand the relationship between superclasses and subclasses (10 minutes)

Background material:

-

Classes:

- Can extend exactly one superclass (which may itself extend another class)

- Can implement multiple interfaces

- Inherit fields and methods from its superclass, can also override methods

- Can be concrete (provide an implementation for all methods) or abstract (declare methods that must be implemented by subclasses). More on abstract classes later.

Here is how a class is defined in Java:

package io.github.neu-pdi.cs3100.iot.lights;

public class TunableWhiteLight extends DimmableLight {

private int startupColorTemperature;

public TunableWhiteLight(String deviceId, int startupColorTemperature, int startupBrightness) {

super(deviceId, startupBrightness);

this.startupColorTemperature = startupColorTemperature;

}

/**

* Turn on the light.

* Sets the color temperature to the startup color temperature.

*/

@Override

public void turnOn() {

setColorTemperature(startupColorTemperature);

// With the color temperature set, we can now turn on the light.

super.turnOn();

}

/**

* Set the color temperature of the light.

* @param colorTemperature The color temperature to set the light to, in degrees Kelvin.

*/

public void setColorTemperature(int colorTemperature) {

// ...

}

/**

* Get the color temperature of the light.

* @return The color temperature of the light, in degrees Kelvin.

*/

public int getColorTemperature() {

// ...

}

}

This code snippet declares our TunableWhiteLight class, which extends DimmableLight. Here are some key syntax points to note:

-

We specify the superclass of

TunableWhiteLightwith theextendskeyword. -

We declare a constructor that initializes the

startupColorTemperaturefield. -

We declare some new methods (

setColorTemperatureandgetColorTemperature), and override theturnOnmethod ofDimmableLight. -

Each of these methods is

public, which means they can be called by other classes. -

The other visibility modifiers are

privateandprotected.privatemeans the method can only be called by other methods in the class.protectedmeans the method can be called by other methods in the class, and by subclasses.

-

If you don't specify a visibility modifier, it defaults to

package-private, which means the method can be called by other methods in the same package. This is generally regarded as a bad practice (and bad language feature) because it makes it hard to reason about the accessibility of methods, and we suggest you avoid it.

On the keyword super:

-

superrefers to the direct superclass the same way callingthisrefers to the present class. In this case callingsuperinTunableWhiteLightrefers toDimmableWhiteLight -

Use case 1: fields that are common between all instances of the superclass can be abstracted by calling the constructor of the superclass in the first line of the subclass constructor. Based on how it is used above, the constructor of

DimmableLightwould look something like

public class DimmableLight extends Light {

protected int startupBrightness;

public DimmableLight(String deviceId, int startupBrightness) {

super(deviceId);

this.startupBrightness = startupBrightness;

}

...

}

- Use case 2: you might wish to defer to the implementation of your superclass after some work in your subclass. In that case, use

super.[someMethod]()asturnOndoes

Some rules for overriding methods:

- We use the

@Overrideannotation to indicate that we are overriding a method from the superclass. This is not strictly required by the JVM, but is helpful for readability. It also allows the compiler to catch some errors: if you put@Overrideon a method that doesn't actually override a superclass method, the compiler will generate an error.

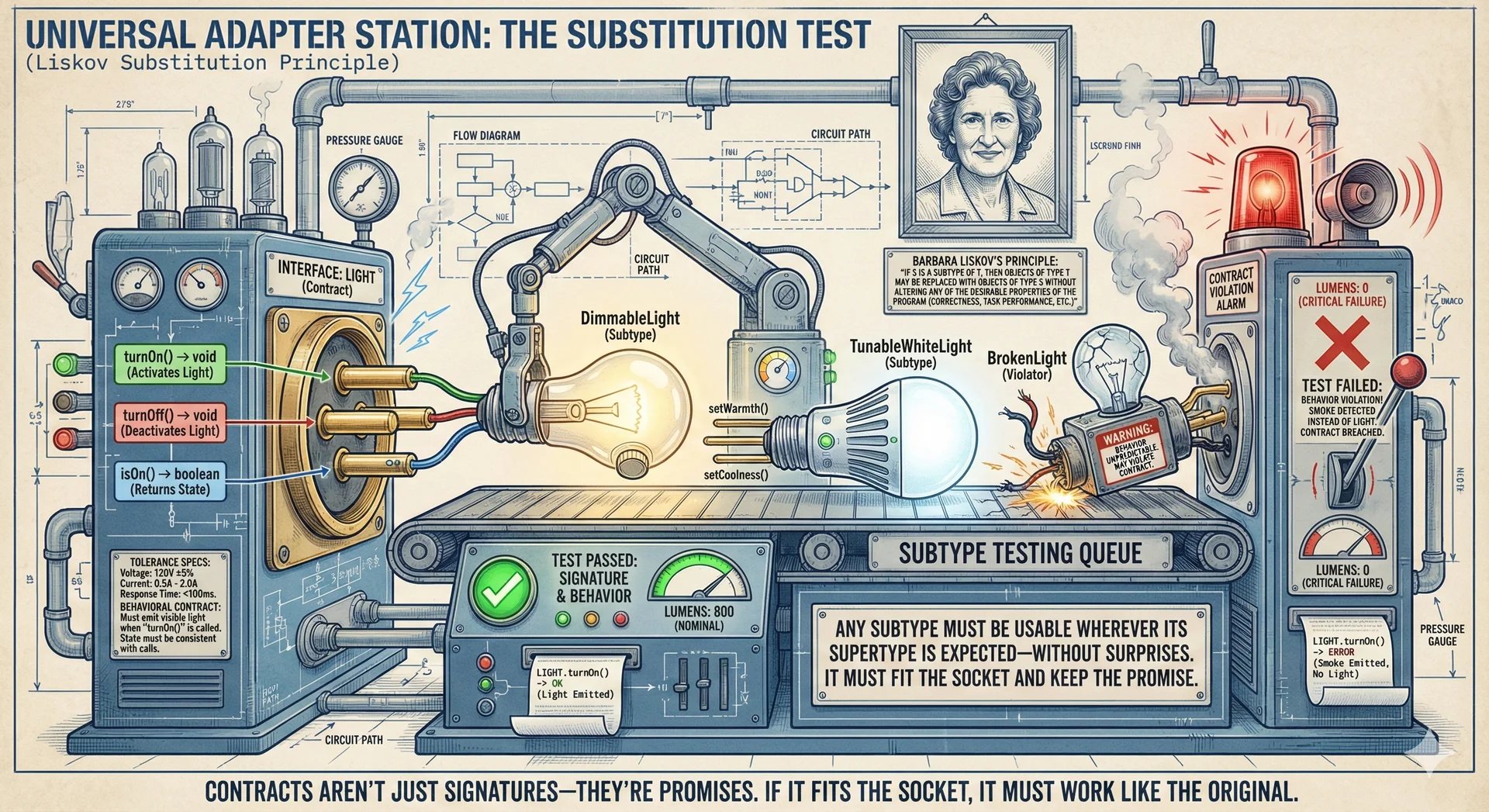

Each type in the hierarchy must (by our rule, not by the Java language spec) satisfy the Liskov Substitution Principle:

- The method signatures (parameters, return type) must be the same as the method it overrides. This is enforced by the compiler.

- The behavior of the method must be the same as the method it overrides. This is not enforced by the compiler, but is a good design principle.

- There is an implicit specification that the method

turnOnmust turn on the light. If a subclass overrides this method and does not turn on the light, it is violating the Liskov Substitution Principle. - This is important because it allows us to substitute a superclass for a subclass in our program.

- There is an implicit specification that the method

- Any properties that hold for the superclass must also hold for the subclass.

- Example property: If the light is on, the method

isOnmust return true. If the light is off, the methodisOnmust return false.

- Example property: If the light is on, the method

- We'll return to this principle later when we discuss polymorphism and specification.

Java allows assignment of a subclass to a superclass reference:

Light[] lights = new Light[2];

TunableWhiteLight light = new TunableWhiteLight("light-1", 2700, 100);

lights[0] = light;

TunableWhiteLight light2 = new TunableWhiteLight("light-2", 2200, 100);

lights[1] = light2;

for (Light l : lights) {

l.turnOn();

}

In this code snippet, we declare an array of Light references, and assign a TunableWhiteLight to the first element.

This is allowed because a TunableWhiteLight is a Light, and thus a Light is a TunableWhiteLight.

We wrote this somewhat verbosely to make it clear that we are assigning a TunableWhiteLight to a Light reference, but we could have written this more concisely:

Light[] lights = new Light[] {

new TunableWhiteLight("light-1", 2700, 100),

new TunableWhiteLight("light-2", 2200, 100)

};

for (Light l : lights) {

l.turnOn();

}

To access the TunableWhiteLight methods, we need to cast the Light reference to a TunableWhiteLight reference:

TunableWhiteLight light2 = (TunableWhiteLight) lights[1];

light2.setColorTemperature(2200);

This snippet could also be written more concisely:

((TunableWhiteLight) lights[1]).setColorTemperature(2200);

Explain the role of interfaces and abstract classes in a Java class hierarchy (10 minutes)

Sometimes we want to declare a set of behaviors that must be implemented by all subclasses, but we don't want to provide a concrete implementation for those behaviors. There are two ways to do this: interfaces and abstract classes.

Interfaces

- Interfaces:

- Define a set of methods that a class must implement.

- Can extend one or more interfaces.

- Can be implemented by multiple classes.

- Can provide a default implementation for some methods (but the semantics are messy and we don't recommend it)

- Cannot be instantiated directly.

Here is an example of an interface:

public interface IoTDevice {

/**

* Identify the device to a human (e.g., flash a light, spin a fan, beep a speaker).

*/

public void identify();

/**

* Check if the device is available.

* @return true if the device is connected and available, false otherwise.

*/

public boolean isAvailable();

}

Abstract classes

- Abstract classes:

- Define a set of methods that a class must implement.

- Can extend one or more classes.

- Can provide a default implementation for some methods

- Cannot be instantiated directly.

A common pattern in Java is to pair an interface with a skeletal implementation (also called an "abstract base class"). This gives callers flexibility: they can extend the abstract class for convenience, or implement the interface directly if they need different behavior. You'll see this pattern throughout the Java standard library in upcoming lectures with classes like AbstractList, AbstractMap, and AbstractCollection.

Here is an example of an abstract class that provides a skeletal implementation of IoTDevice:

public abstract class BaseIoTDevice implements IoTDevice {

protected String deviceId;

protected boolean isConnected;

public BaseIoTDevice(String deviceId) {

this.deviceId = deviceId;

this.isConnected = false;

}

/**

* Check if the device is available.

* @return true if the device is connected, false otherwise.

*/

@Override

public boolean isAvailable() {

return this.isConnected;

}

/**

* Identify the device to a human (e.g., flash a light, spin a fan, beep a speaker).

* Each device type must implement this differently based on its hardware.

*/

public abstract void identify();

}

Key notes on abstract classes:

- Fields in abstract classes are often

protectedso they can be accessed by subclasses - We implement methods common between all subclasses to reduce duplication (like

isAvailable()) - Not all methods from the interface need to be implemented by abstract classes since they are not directly instantiated, but those methods will still be required in concrete classes that

extendthem - We can use

abstract methodssuch asidentify()in abstract classes to enforce that subclasses implement behaviors that depend on their specific characteristics (in this case, hardware)

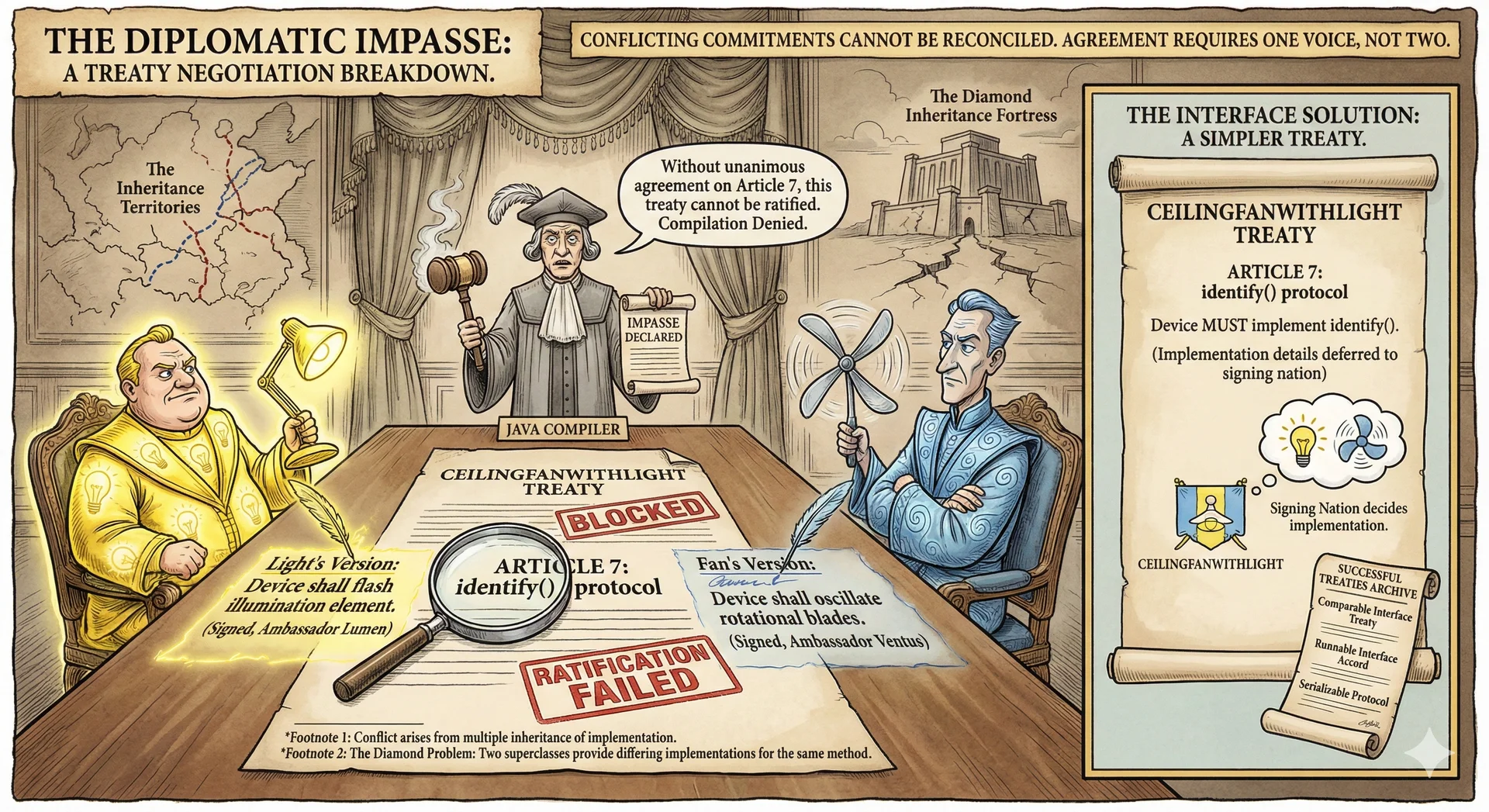

Why Java doesn't allow multiple class inheritance

Some objects legitimately belong to multiple categories (e.g., a ceiling fan with a built-in light is both a Light and a Fan). However, multiple class inheritance creates ambiguity when both parent classes implement the same method differently:

This is called the "diamond problem." Java avoids it by restricting multiple inheritance to interfaces:

- Interfaces don't provide implementations (usually), so there's no ambiguity

- The implementing class must provide the implementation

- This forces explicit design decisions rather than implicit (and potentially confusing) behavior

Describe the JVM's implementation of dynamic dispatch (10 minutes)

Recall that we can assign a subclass to a superclass reference:

Light[] lights = new Light[] {

new TunableWhiteLight("light-1", 2700, 100),

new DimmableLight("light-2", 100)

};

We said that this assignment is allowed because a TunableWhiteLight and DimmableLight are both Light, and thus a Light is a TunableWhiteLight or DimmableLight. But, how does the JVM know which method to call?

"Dynamic dispatch" is the process by which the JVM determines which method to call at runtime:

for (Light l : lights) {

l.turnOn(); // This will call the turnOn method of the actual type of l, which may be TunableWhiteLight, DimmableLight, or some other subclass.

}

Notice how even at the same call-site, the JVM will call the turnOn method of the actual type of l.

Here is how the JVM implements dynamic dispatch to call method on object of type :

- If contains a declaration of , use that.

- If has a superclass that contains a declaration of , use that. If not, continue recursively with 's superclass.

- If no other declaration is found, and is provided as a default interface method, use that (default interface methods are a confusing feature that we will not go into).

This is called "dynamic dispatch" because the method to call is determined at runtime, rather than at compile time. Consider the following example:

Light l = new TunableWhiteLight("living-room", 2700, 100);

l.turnOn(); // This will call the turnOn method of the actual type of l, which is TunableWhiteLight.

((DimmableLight) l).turnOn(); // Still calls turnOn method of TunableWhiteLight, because when it runs, that's the type of l.

Regardless of the type of the variable in our code, the actual type at runtime is used to determine which method to call.

Describe the difference between static methods and instance methods (5 minutes)

Some methods are declared as static, which means they are associated with the class itself, rather than an instance of the class.

This is a snippet of code from our TunableWhiteLight class, now including a static method:

public class TunableWhiteLight extends DimmableLight {

//...

/**

* Convert a color temperature in degrees Kelvin to a color temperature in mireds.

* @param degreesKelvin The color temperature in degrees Kelvin.

* @return The color temperature in mireds.

*/

public static int degressKelvinToMired(int degreesKelvin) {

return 1000000 / degreesKelvin;

}

//...

}

This static method is associated with the TunableWhiteLight class, not an instance of the class.

To invoke it, we use the class name:

TunableWhiteLight.degressKelvinToMired(2700);

Static methods are statically bound, unlike instance methods which are dynamically bound. At the time that you write and compile your code, the method to call is known (no runtime lookup is needed).

Describe the JVM exception handling mechanism (5 minutes)

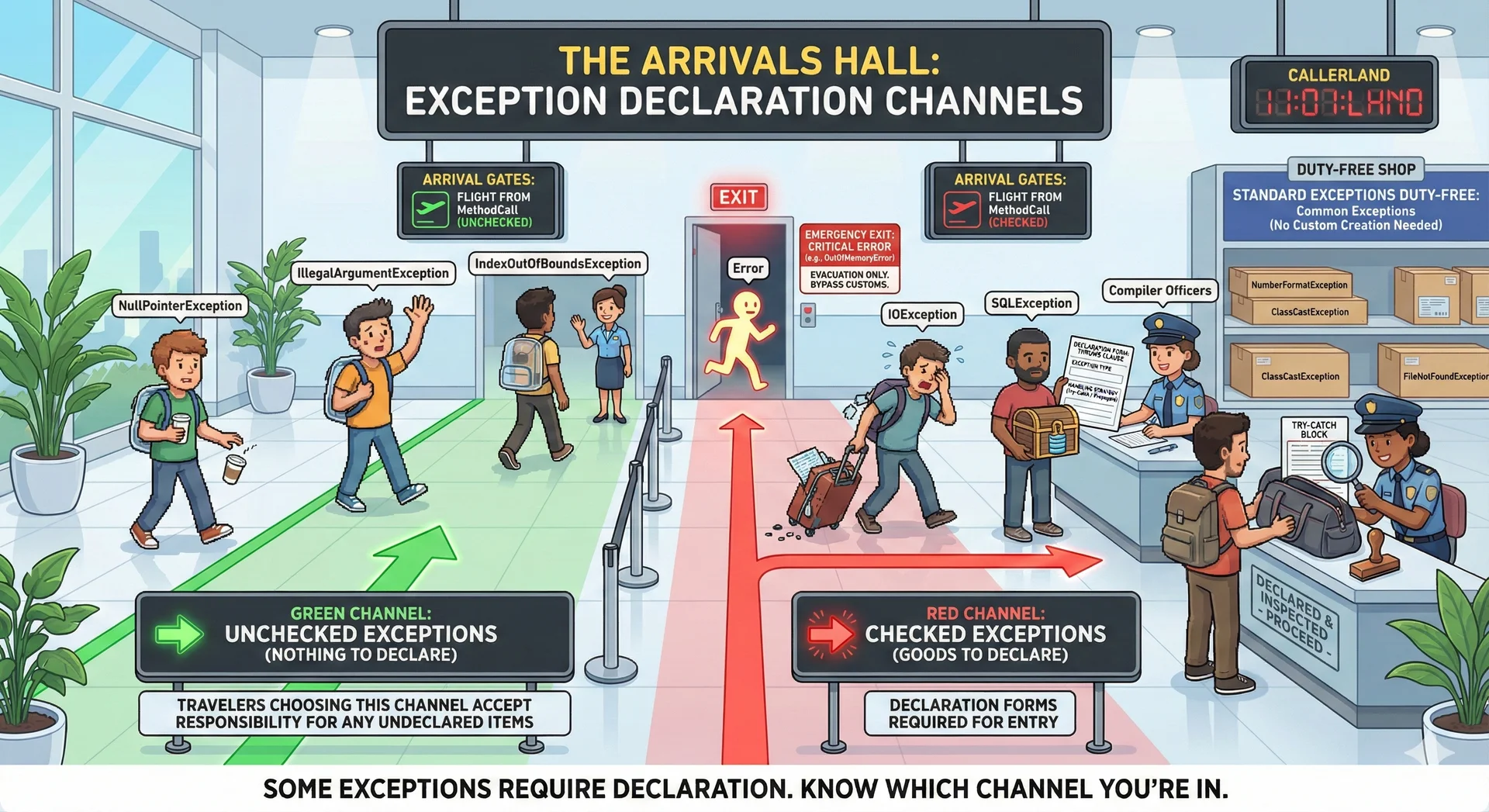

All exceptions in Java are instances of the Throwable class. It is important to note that, since Java is a statically typed language, we can distinguish between different kinds of exceptions.

There are two subclasses of Throwable: Exception and Error.

An Error is an exception that is typically fatal, and detected by the JVM itself, although you can also throw them explicitly. For example, the JVM throws an OutOfMemoryError if it runs out of memory, or a StackOverflowError if the stack overflows (too much recursive function calling). These are not expected to be caught by application code. It is generally bad practice to throw an Error in your code.

Exceptions are further divided into two categories: checked and unchecked.

uncheckedexceptions are those that are not required to be caught by calling code (all subclasses ofRuntimeException)checkedexceptions are those that are required to be caught by calling code (all subclasses ofExceptionthat are not subclasses ofRuntimeException)

This is different than Python, where all exceptions are unchecked.

By making this distinction, an API can require that certain exceptions are caught, and the compiler will enforce that requirement.

This class diagram shows the relationship between the classes, along with four example exceptions:

You should only use exceptions for exceptional cases, for example, this is not a good use of an exception:

try {

Light[] lights = {

new TunableWhiteLight("light-1", 2700, 100),

new TunableWhiteLight("light-2", 2200, 100)

};

int i = 0;

while(true){ // Infinite loop breaks when i is out of bounds of the array

lights[i].turnOn();

i++;

}

} catch (ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException e) {

// Do nothing

}

Recognize common Java exceptions and when to use them (5 minutes)

While you could create a specialized exception for every possible error condition, this would be anithetical to the idea of reusing code. Instead, we favor the use of standard exceptions

Here are some common exceptions and when to use them:

IllegalArgumentException: When a method is passed an illegal or inappropriate argument.NullPointerException: When a method is passed a null argument that is not expected.IllegalStateException: When an object is in an inappropriate state for a method to perform its task.IndexOutOfBoundsException: When an index is out of bounds.UnsupportedOperationException: When an operation is not supported by an object.

Each method should check parameters for validity and throw an appropriate exception if the parameters are invalid. For example:

/**

* Set the color temperature of the light.

* @param colorTemperature The color temperature to set the light to, in degrees Kelvin.

* @throws IllegalArgumentException if the color temperature is outside the valid range.

*/

public void setColorTemperature(int colorTemperature) {

if (colorTemperature < 1000 || colorTemperature > 10000) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Color temperature in degrees Kelvin must be between 1,000 and 10,000");

}

// ...

}