Interpreting Requirements

Explain the overall purpose of requirements analysis (10 minutes)

Let's start with a story that some of us professors have seen happen again and again. A professor approaches a student with a "simple" request:

"I need a system to help my TAs grade programming assignments more efficiently. Can you build something by next month?"

Sounds straightforward, right? But what does "efficiently" mean? What specific problems are the TAs facing? What does the professor consider "grading"? Is it just running test cases, or does it include providing feedback, handling regrade requests, and tracking statistics?

This is where requirements analysis comes in. Requirements analysis is the process of discovering, documenting, and validating what a system should do. It's the bridge between a vague idea ("make grading better") and a concrete plan for what to build.

Why Requirements Analysis Matters

Consider what happens without proper requirements analysis:

Version 1: What the developer built based on initial conversation

- The system shall automatically run test cases on student submissions

- The system shall return a numerical score as a percentage

- The system shall store the final grade

Version 2: What the professor actually needed

- The system shall run automated tests on student code

- The system shall check code style compliance

- The system shall enable inline commenting on specific lines of code

- The system shall preserve previous grading when students resubmit

- The system shall notify original graders of resubmissions

- The system shall prevent the same grader from repeatedly grading the same student

- The system shall randomly sample 10% of graded work for quality review

- The system shall track grader workload for fair distribution

- The system shall support multi-stage regrade requests with escalation

- The system shall integrate with the university's grade submission system

The difference between these two specifications might represent hundreds of hours of wasted work, frustrated users, and missed deadlines.

Requirements analysis failures have ocurred since humans have been building products (software or otherwise). Here is a proto-meme, versions of which have reportedly circulated since the early 1900's:

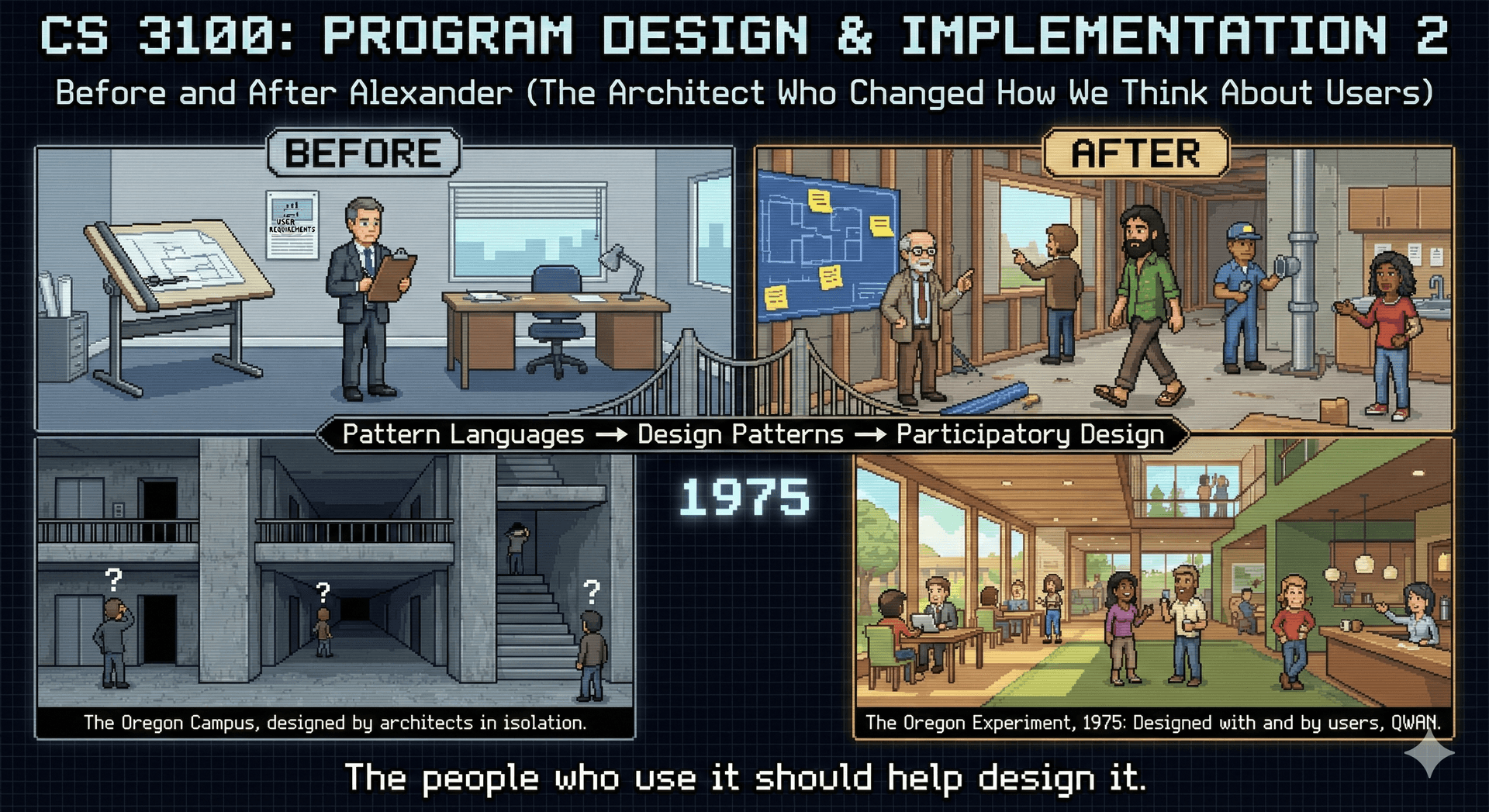

(Attribution: Christopher Alexander, et al. "The Oregon Experiment", 1975, page 44 - interestingly enough, he uses this example to illustrate the importance of engaging users in the design process for designing academic buildings; it would not be for several years before his ideas would be widely popularized in the field of object-oriented design.)

(Attribution: Christopher Alexander, et al. "The Oregon Experiment", 1975, page 44 - interestingly enough, he uses this example to illustrate the importance of engaging users in the design process for designing academic buildings; it would not be for several years before his ideas would be widely popularized in the field of object-oriented design.)

The Cost of Getting Requirements Wrong

The cost of fixing requirements errors grows exponentially over time:

- During requirements phase: 1x cost to fix

- During design phase: 5x cost to fix

- During implementation: 10x cost to fix

- During testing: 20x cost to fix

- After deployment: 100x cost to fix

Why? Because each phase builds on the previous one. A misunderstood requirement affects the design, which affects the implementation, which affects the tests, which affects user training and documentation. Work that you have already done might need to be discarded or rewritten. In the worst case scenario, you never fully undertand the requirements of your users, and leave them unsatisfied.

Requirements Analysis is Not Just "Asking What They Want"

If requirements analysis were just asking users what they want, it would be easy. But users often:

- Don't know what they want until they see it

- Can't articulate their needs clearly

- Focus on solutions instead of problems

- Have conflicting needs with other stakeholders

- Change their minds as they learn more

More fundamentally, treating users as mere sources of requirements misses a crucial insight: users are experts in their own domain. They understand their work, their pain points, and their context better than any developer ever could. The goal isn't to extract requirements from them like mining ore from rock—it's to engage them as partners in the design process.

This idea has deep roots. In the 1970s, architect Christopher Alexander argued that the people who inhabit spaces should participate in designing them. He observed that the best buildings weren't created by architects working in isolation, but emerged from collaboration between professionals and the people who would actually use the spaces. Alexander developed the concept of "pattern languages"—shared vocabularies that allow experts and users to communicate about design. This work later influenced software design patterns, but the participatory philosophy behind it is equally important.

Consider the difference between these two approaches:

Extractive Approach (treating users as requirement sources):

- Developer: "What features do you need?"

- Professor: "I need automated grading."

- Developer: "OK, I'll build an autograder."

- [Much Later...]

- Professor: "This isn't what I wanted at all!"

Participatory Approach (treating users as design partners):

- Developer: "Tell me about your grading challenges."

- Professor: "I spend weekends grading, and students complain about inconsistency."

- Developer: "Let's explore what 'grading' means in your course. Can you show me?"

- Professor: [Shows process] "I check correctness, but also code style, approach..."

- Developer: "What if we could automate the mechanical parts, letting you focus on the pedagogical aspects?"

- Professor: "Oh! That would change how I design assignments..."

- Developer: "Let's sketch some possibilities together..."

In the participatory approach, requirements don't just flow from user to developer. Instead, possibilities emerge from collaboration. The professor learns what's technically feasible, the developer learns what's pedagogically important, and together they discover solutions neither would have imagined alone.

For example, a collaborative investigation might reveal that:

- The real bottleneck is providing meaningful feedback, not calculating scores

- TAs spend time on repetitive feedback that could be templated

- Students need feedback quickly to learn, but TAs need to batch for efficiency

- The inconsistency problem is actually about unclear rubrics, not TA variation

- The workload problem is actually about uneven distribution, not total volume

Good requirements analysis is like being a detective working with witnesses, not interrogating them. You gather clues together, explore patterns, test hypotheses collaboratively, and gradually build a shared understanding of both the problem and potential solutions.

Consider this requirements conversation that demonstrates participatory discovery:

Professor: "I need the system to be fair."

You: "What does 'fair' mean to you?"

Professor: "Well, students complain that some TAs grade harder than others."

You: "How would you like to address that?"

Professor: "Maybe... standardize the grading somehow?"

You: "Would a rubric help? Or do you want multiple graders per assignment? Or statistical normalization?"

Professor: "Oh! I didn't think of those options. Actually, now that you mention it, the real problem might be that TAs interpret my rubric differently..."

You: "What if TAs could see each other's grading decisions on example submissions?"

Professor: "Like a calibration exercise? That's brilliant! We could do that before each assignment!"

Notice how the conversation evolves from a vague value ("fairness") through surface solutions ("standardize") to deeper understanding (rubric interpretation) and finally to novel solutions (calibration exercises). Neither party had this solution in mind at the start—it emerged from their collaboration.

This participatory approach also helps build what we'll later call a domain model—a shared understanding of the concepts, relationships, and rules that govern the problem space. When users and developers build this model together, they create a common language. The professor stops saying "the system should be fair" and starts saying "we need inter-rater reliability." The developer stops thinking in terms of databases and starts thinking in terms of rubrics, feedback, and learning outcomes.

This shared language is crucial because it allows all stakeholders to participate meaningfully in design decisions throughout the project. As we'll see when we discuss user-centered design, the best systems emerge from ongoing collaboration, not from requirements documents thrown over the wall.

Enumerate and explain 3 major dimensions of risk in requirements analysis (15 minutes)

Requirements analysis is fundamentally about managing risk. Every requirement carries risks, and understanding these risks helps you focus your effort where it matters most. Let's examine three critical dimensions of requirements risk.

Risk Dimension 1: Understanding (How well do we understand what's needed?)

Understanding risk occurs when there's ambiguity, complexity, or disagreement about what a requirement means.

Low Understanding Risk:

"The system shall record the UTC timestamp when a submission is received."

This is clear, unambiguous, and everyone understands what a timestamp is. It even avoids the ambiguity of "local time" vs "UTC".

High Understanding Risk:

"The system shall ensure grading quality through meta-reviews."

What's a meta-review? Who does it? When? What constitutes "quality"? Different stakeholders might have completely different interpretations:

Professor's interpretation:

- Meta-reviews are spot-checks by senior TAs

- Randomly sample 10% of graded work

- Focus on consistency across graders

- Happen after grading is complete

TA's interpretation:

- Meta-reviews are second opinions on difficult cases

- Every assignment gets reviewed by two graders

- Discrepancies are reconciled through discussion

- Happen during the grading process

Student's interpretation:

- Meta-reviews are appeals to a higher authority

- Available when students disagree with grades

- Provide an impartial re-evaluation

- Can overturn original grades

Strategies for Reducing Understanding Risk:

- Ask for concrete examples: "Can you walk me through a specific meta-review?"

- Create prototypes: "Is this what you mean by meta-review?"

- Define terms explicitly: Create a glossary

- Look for inconsistencies: Different stakeholders using the same term differently

Risk Dimension 2: Scope (How much are we trying to build?)

Scope risk relates to the size and complexity of what you're committing to build. It's not just about feature count—it's about interdependencies, edge cases, and hidden complexity.

A professional skill: Negotiating scope. When requirements exceed available time or resources, you need to negotiate priorities with stakeholders. This isn't about saying "no"—it's about collaborative problem-solving: "Given our constraints, how do we deliver the most value?" The ability to advocate for realistic scope while understanding stakeholder priorities is essential in any technical collaboration, whether you're working with a manager, a research advisor, or a client.

Low Scope Risk:

"Students have a fixed number of late tokens, and can apply late tokens before the deadline, each token allowing at 24-hour extension."

This is a small, isolated change with clear boundaries. Note: it is still important to think through the implications of the requirement, and to consider how it might interact with other requirements (e.g., "Self reviews").

High Scope Risk:

"Students can request regrades for any grading decision, which can be escalated to instructors or meta-graders"

This sounds like one feature, but unpack what it really means:

Visible requirements:

- Students can request regrades

- Requests include justification

- Original grader reviews requests

- Decisions can be appealed

Hidden requirements that emerge during analysis:

- Who can request regrades? (Only the student? Team members? Anyone?)

- When can they request? (Immediately? After cooling period? Before finals?)

- How many requests allowed? (One per assignment? Three per semester?)

- What's the escalation path? (Grader → Meta-grader → Instructor?)

- What prevents gaming? (Students requesting until they get an easy grader?)

- How are group assignments handled? (One request per group? Individual?)

- What about concurrent modifications? (Student requests while TA is grading?)

- What audit trail is needed? (Who changed what grade when and why?)

Each question represents additional scope. What seemed like one feature is actually dozens of interconnected decisions.

Managing Scope Risk:

- Break down features into smallest possible units

- Identify dependencies explicitly

- Look for hidden workflows (what happens when things go wrong?)

- Prioritize ruthlessly: What's truly essential vs. nice-to-have?

- Plan for incremental delivery

Risk Dimension 3: Volatility (How likely are requirements to change?)

Volatility risk comes from requirements that are likely to change during or after development.

A professional skill: Adaptability. Requirements will change—this is not a failure of requirements analysis, but a reality of complex work. The question isn't whether to expect change, but how to respond professionally when it happens. Adaptability means designing systems that can evolve, communicating clearly when changes affect timelines, and maintaining composure when priorities shift. These skills matter in any technical context—not just software engineering.

Low Volatility Risk:

"Use the university's standard letter grading scale (A, A-, B+, B, B-, C+, C, C-, D+, D, D-, F)"

This has been stable for decades and is unlikely to change.

High Volatility Risk:

"Integrate with the university's new AI-powered plagiarism detector that is currently in contract negotiations with three different vendors, managed by ITS"

The hypothetical AI tool is still being developed, its API is likely unstable, and the university is considering three different vendors. The organization managing its implementation has no reporting structure to you, the developer, your client, the professor, or the students. Here are examples of how this requirement might evolve over time:

Week 1 Requirement:

- The system shall check submissions for plagiarism

- The system shall report a simple yes/no result

Week 3 Requirement (after vendor demo):

- The system shall analyze similarity between submissions

- The system shall provide a similarity percentage

- The system shall highlight matched sections

- The system shall compare against a corpus of previous submissions

Week 5 Requirement (after legal review):

- The system shall obtain student consent before plagiarism checking

- The system shall allow students to opt-out of corpus inclusion

- The system shall be entirely hosted on Microsoft Azure

- The system shall maintain audit logs of who accessed plagiarism reports

Week 7 Update:

- Entire feature put on hold pending AI Ethics Committee review

Week 10 Update:

- Sub-committee is formed to design more detailed requirements that satisfy the requests of the Office of Information Security

Sources of Volatility:

- External dependencies (APIs, tools, services)

- Regulatory requirements (FERPA, GDPR, accessibility)

- Political factors (university politics, competing interests across organizational units)

- Technical uncertainty (new technologies, unproven approaches)

- Market changes (competitive pressure, user expectations)

Managing Volatility Risk:

- Isolate volatile requirements behind interfaces

- Build the stable core first

- Design for flexibility in areas likely to change

- Defer commitment on volatile requirements when possible

- Document assumptions explicitly

Combining Risk Dimensions

The riskiest requirements are those that score high on multiple dimensions:

"The system shall use machine learning to automatically assign partial credit in a way that's pedagogically sound and legally defensible."

Understanding Risk: HIGH

- What is "pedagogically sound"?

- What makes something "legally defensible"?

- What kind of ML? Trained on what data?

Scope Risk: HIGH

- Need training data collection and curation

- ML model development and training pipeline

- Evaluation metrics and validation process

- Legal review and compliance framework

- Appeals and explanation system

- Continuous model updating and monitoring

Volatility Risk: HIGH

- ML models will evolve with new techniques

- Legal requirements vary by jurisdiction and change over time

- Pedagogical best practices are actively debated and evolving

- Training data availability and quality will change

- All of the same organizational and political factors from the last example still appl

When you encounter high-risk requirements, you have several options:

- Clarify: Reduce understanding risk through analysis

- Simplify: Reduce scope risk by finding simpler solutions

- Stabilize: Reduce volatility risk by fixing interfaces

- Defer: Push high-risk items to later releases

- Eliminate: Question if the requirement is truly needed

Identify the stakeholders of a software module, along with their values and interests (15 minutes)

A stakeholder is anyone who is affected by the system or can affect its success. Missing a key stakeholder is like designing a building without talking to the people who will live in it—you might create something architecturally impressive that nobody can actually use.

Who Do We Interview? Requirements Gathering as Long-Term Risk Management

Requirements gathering is often treated as a one-time activity at project start. But requirements are the foundation that all code builds on - getting them wrong is the most expensive mistake in software engineering.

Consider who might be missing from your interviews:

- Do you only talk to current users? What about those who would use the system if it worked for them?

- Do you interview the manager, or also the workers whose jobs will change?

- Do you consider future stakeholders - regulators, acquirers, international users?

Each missing perspective is a risk that compounds over time. The system gets built, deployed, scaled - and then a missed stakeholder emerges. The cost to accommodate them in year 5 is orders of magnitude higher than in month 1.

Identifying future stakeholders is an important exercise in long-term risk management. If you are building an app that has a "success disaster" (becomes very popular), you will likely suddenly find yourself with a large new set of users who may not have been well-considered in the initial requirements gathering, and who will expect specific features and behaviors that were not considered in the initial requirements gathering. Considering who these potential future users are (and hypothesizing about the scope of what their needs might be) helps to manage the risk of these requirements suddenly appearing through effective architectural design (we'll get to this in lecture 19).

Let's identify stakeholders for our grading system and understand their often-conflicting values. Note: these are not necessarily the only stakeholders, and not necessarily the most important stakeholders, the list of stakeholders and their values is for illustration purposes only.

Primary Stakeholders (Direct Users)

Students

- Primary concern: "Will I get the grade I deserve?"

- Values: Fairness, transparency, timeliness

- Desires:

- Fast feedback to support learning

- Consistent grading across all TAs

- Clear explanation of point deductions

- Fair and accessible regrade process

- Privacy of code and grades from other students

- Fears:

- Biased or subjective grading

- Lost submissions with no proof of submission

- Getting the "harsh" TA

- No recourse for grading errors

- Public embarrassment from visible failures

Graders (Teaching Assistants)

- Primary concern: "Can I grade fairly without spending my entire weekend?"

- Values: Efficiency, accuracy, workload management

- Desires:

- Clear rubrics that minimize subjective decisions

- Automated testing for objective components

- Ability to reuse common feedback comments

- Fair distribution of grading workload

- Protection from aggressive student complaints

- Fears:

- Overwhelming workload during deadline crunches

- Hostile regrade requests questioning their competence

- Being labeled as the "harsh" or "easy" TA

- Making mistakes that affect students' futures

Instructors

- Primary concern: "Are students learning and being evaluated fairly?"

- Values: Educational outcomes, academic integrity, oversight

- Desires:

- Grading that aligns with learning objectives

- Detection of cheating and plagiarism

- Ability to monitor TA performance

- Statistical reports on class performance

- Minimal time spent on administrative tasks

- Fears:

- Grade complaints escalated to department chair

- Inconsistent grading making them look incompetent

- Missing serious academic integrity violations

- Spending time on administration instead of teaching

Secondary Stakeholders (Indirect Users)

Meta-Graders (Senior TAs)

- Primary concern: "How do I ensure grading quality without redoing all the work?"

- Values: Quality control, mentorship, conflict resolution

- Desires:

- Efficient mechanisms to review grader work

- Clear escalation paths for complex issues

- Authority to override when necessary

- Tools to train and mentor new TAs

Department Administrator

- Primary concern: "Are we following university policies and using resources efficiently?"

- Values: Compliance, resource management, record keeping

- Desires:

- FERPA compliance for grade privacy

- Complete audit trails for grade changes

- TA workload reports for payroll processing

- Seamless integration with university systems

IT Support

- Primary concern: "Will this system create support tickets at 2 AM during finals week?"

- Values: Stability, security, maintainability

- Desires:

- Minimal server resource requirements

- Standard university authentication (SSO)

- Clear error messages that users can understand

- Documented backup and recovery procedures

Hidden Stakeholders (Often Forgotten)

Parents (especially for undergraduate courses)

- May call demanding grade explanations

- Expect transparency about their child's performance

- Don't have direct access but influence students and administrators

Future Employers

- Rely on grades as signals of competence

- Expect grades to reflect actual skills

- Never interact with system but are affected by its outputs

Accreditation Bodies

- Require documentation of assessment methods

- Audit grading practices periodically

- Can shut down programs that don't meet standards

Conflicting Stakeholder Interests

The challenge is that stakeholder interests often directly conflict. Resolving these conflicts is fundamentally a negotiation skill—understanding what each party truly needs (not just what they initially ask for) and finding creative solutions that address underlying concerns. This skill applies whether you're building software, collaborating on research, or working on any team project.

Student vs. TA Conflict:

- Students want unlimited regrade requests for fairness

- TAs want protection from frivolous requests that waste time

Instructor vs. Student Conflict:

- Instructors want detailed analytics on performance

- Students want privacy of their grades and mistakes

TA vs. Instructor Conflict:

- TAs want fully automated grading for efficiency

- Instructors want nuanced evaluation of understanding

Student vs. Student Conflict:

- Fast students want immediate feedback

- TAs want to batch grading for efficiency, which delays feedback

Administrator vs. TA Conflict:

- Administrators want detailed audit logs for compliance

- TAs want quick, simple grade entry without overhead

Using Stakeholder Analysis

Understanding stakeholders helps you:

- Prioritize requirements: Weight instructor needs higher than IT preferences

- Resolve conflicts: Find creative solutions that balance competing needs

- Communicate effectively: Frame features in terms of stakeholder values

- Anticipate resistance: Know who might oppose changes and why

For example, when designing the regrade request feature:

Balancing stakeholder needs:

- Student desire: Easy ability to request regrades

- TA protection: Limits on number of requests and how long they can be requested

- Instructor oversight: Detailed justification required

- Admin compliance: Complete audit trail of all regrade activities

Describe methods to elicit users' requirements (15 minutes)

Getting requirements from stakeholders is harder than it seems. Users often don't know what they want, can't articulate what they know, or focus on solutions instead of problems. Let's explore different elicitation techniques, each with its own strengths.

Method 1: Interviews

One-on-one conversations with stakeholders to understand their needs, workflows, and pain points.

Structured Interview Example with a TA:

Q: Walk me through grading a typical assignment from start to finish.

"I download submissions from Canvas, run them locally, open a spreadsheet, test each function manually..."

Q: What takes the most time?

"Setting up the test environment for each student's code, and writing the same feedback over and over."

Q: What mistakes do you worry about making?

"Forgetting to test an edge case, being inconsistent between students, losing track of who I've graded."

Q: Tell me about the last time grading went really badly.

"A student submitted at 11:59 PM, I graded at midnight, but then they claimed they submitted again at 12:01 AM and I graded the wrong version..."

Interview Techniques:

- Open-ended questions: "Tell me about..." instead of "Do you..."

- Critical incident technique: "Describe a time when things went wrong"

- Probing: "Why is that important?" "Can you give an example?"

- Silence: Let people think and elaborate

Interview Pitfalls to Avoid:

- Leading questions: "Wouldn't automated grading be better?" → "How do you decide grades?"

- Technical jargon: "How do you handle race conditions?" → "What happens if two students submit at the same time?"

- Accepting vague answers: When they say "user-friendly," ask "What would make it user-friendly for you specifically?"

Method 2: Observation (Ethnography)

Watch users perform their actual work to understand what they really do (versus what they say they do).

Observation Session: TA Grading Lab

Timeline of observed activities:

- 2:00 PM - TA logs into Canvas, downloads submission ZIP file

- 2:05 PM - Discovers some submissions are .tar.gz format (unexpected)

- 2:08 PM - Writes quick script to handle multiple archive formats

- 2:15 PM - Opens first submission, realizes it's Python 2 not Python 3

- 2:18 PM - Sets up separate testing environment for Python 2

- 2:20 PM - Manually copies test cases from assignment PDF

- 2:30 PM - Opens spreadsheet, realizes student order doesn't match Canvas

- 2:35 PM - Spends time matching student IDs between systems

- 2:37 PM - Phone notification interrupts flow

- 2:38 PM - Loses track of which submission they were grading

Key Observations:

- File format inconsistency not mentioned in interviews

- Manual test case copying (inefficient and error-prone)

- Constant context switching between tools

- System integration problems (order mismatches)

- Interruptions breaking concentration

Method 3: Workshops and Focus Groups

Bring multiple stakeholders together to discuss requirements and resolve conflicts.

Sample Workshop: "Designing the Regrade Process"

Participants: 2 instructors, 3 TAs, 2 meta-graders, 3 students

Activity 1: Individual Brainstorming (10 minutes)

- Everyone writes ideal regrade process on sticky notes

Activity 2: Affinity Mapping (20 minutes)

- Group similar ideas into clusters:

- "Need justification for regrades"

- "Limit number of requests"

- "Anonymous grading to prevent bias"

Activity 3: Conflict Resolution (20 minutes)

- Student: "We need unlimited regrades for fairness"

- TA: "That would overwhelm us during finals"

- Negotiated compromise: "Three regrades per semester, but serious errors don't count against limit"

Activity 4: Dot Voting (15 minutes)

- Each person gets 5 dots to place on most important features

- Clear priorities emerge from collective voting

Benefits of Group Sessions:

- Stakeholders hear each other's perspectives directly

- Creative solutions emerge from discussion

- Conflicts surface and get resolved early

- Builds buy-in for the solution

Method 4: Prototyping

Build quick mock-ups to make requirements concrete and get specific feedback.

Paper Prototype Session:

Facilitator shows hand-drawn interface

"You want to request a regrade. What would you do?"

Student: "I'd click on my grade... wait, where is it?"

Facilitator draws grade link: "Here. Now what?"

Student: "I click it. What happens next?"

Facilitator shows new paper screen: "You see this form."

Student: "Oh, I have to write why? How much detail?"

Facilitator: "What would be reasonable?"

Student: "Maybe just point to which problem and a brief explanation?"

Digital Prototype Discoveries:

- "Can I see my original submission here?"

- "What if I want multiple problems reviewed?"

- "How do I know if my request was received?"

- "Can I attach screenshots of my code running correctly?"

Method 5: Document Analysis

Study existing documents to understand current processes and requirements.

Documents to Analyze:

- Grading rubrics: Reveal evaluation criteria and point distributions

- Email complaints: Show common pain points and misunderstandings

- Grade appeal forms: Document existing process and requirements

- TA training materials: Expose hidden complexities in grading

- University policies: Define constraints and compliance requirements

- Previous syllabi: Show evolution of grading policies

Example Discovery from Syllabus:

"Regrade requests must be submitted within one week of grades being posted, in writing, with specific reference to the rubric."

Requirements discovered:

- Time limit on regrade requests (1 week)

- Must be written (not verbal)

- Must reference rubric (rubric must be visible to students)

- "Posted" implies delay between grading and student visibility

Method 6: Scenarios and Use Cases

Write concrete stories about how the system will be used.

Scenario: End-of-Semester Grade Dispute

Sarah, a senior, needs a B+ to keep her scholarship. She receives a B after the final assignment. Checking her grades, she notices Assignment 3 seems low. She reviews the rubric and believes her recursive solution was incorrectly marked as wrong when it actually works for all test cases.

She initiates a regrade request on December 15th, explaining her case with code examples. The original TA, Tom, is already on winter break. The system automatically escalates to meta-grader Alice, who must respond within 48 hours due to grade submission deadlines. Alice reviews, agrees with Sarah, and updates the grade. The system notifies the instructor, updates the registrar, and logs the entire interaction.

Requirements Revealed:

- Urgency handling for end-of-semester requests

- Escalation when grader unavailable

- Integration with registrar system

- Audit logging for all grade changes

- Time-sensitive response requirements

Combining Methods

The best requirements come from using multiple methods:

- Start broad: Interview stakeholders to understand general needs

- Get specific: Observe actual work to see hidden complexities

- Resolve conflicts: Run workshops with multiple stakeholders

- Validate understanding: Test with prototypes

- Check constraints: Analyze policy documents

- Verify completeness: Walk through detailed scenarios

Red Flags in Requirements Elicitation

Watch out for:

- Only talking to managers: They don't do the actual work

- Leading questions: You'll hear what you want to hear

- Single method: Each method has blind spots

- No iteration: Requirements need refinement

- Missing stakeholders: The quiet ones often have critical needs

- Solution jumping: "We need a database" vs. "We need to track grades"

Remember: Requirements elicitation is not a phase—it's an ongoing conversation. As stakeholders see prototypes and early versions, they'll remember things they forgot to mention, realize what they actually need, and change their minds about what's important.

Summary

Requirements analysis is the critical bridge between vague human needs and precise system specifications. It's fundamentally about managing three types of risk: understanding (do we know what they mean?), scope (how much are we building?), and volatility (what will change?).

Success requires identifying all stakeholders—not just the obvious users but also the administrators worried about compliance, the IT staff who'll support it, and the future employers who rely on grade integrity. These stakeholders have conflicting values that must be carefully balanced.

Eliciting requirements demands multiple techniques: interviews to hear what people say, observation to see what they actually do, workshops to resolve conflicts, prototypes to make ideas concrete, and document analysis to understand constraints. No single method is sufficient—requirements emerge from the synthesis of all these approaches.

The key insight: Requirements analysis isn't about asking "what do you want?" It's about understanding problems deeply enough to design solutions that stakeholders didn't even know were possible. When done well, it prevents the expensive mistake of building the wrong thing right.